If Not VMware, Then Where?

Exiting VMware: Sentiment, Strategy, and Alternatives

For most organizations, the decision to exit VMware isn’t technical. As a hypervisor, ESX is hard to beat. The motives behind these decisions are usually a mix of financial, strategic, and sentiment-driven factors. Of these, sentiment is important. It may sound like a “sixth sense,” but strategy and even financial decisions can be realigned around it. This isn’t about a purely emotional reaction—it’s about informed opinion.

VMware no longer holds a monopoly on virtualization; there are other strong options:

Public Cloud

One company’s loss is another’s gain. Cloud providers are actively capitalizing on the situation by offering funding and credits to offset migration costs. That’s attractive to budget-conscious customers and helps build goodwill. However, the desire to make the cloud the answer to the problem can lead to overly optimistic TCO calculations. Sentiment plays a role here too—so when your boss expresses a strong desire to “make this work,” you may need to shelve your bottom-up approach to calculating costs. Understanding the agenda and motives of others is critical. Vendors want to sell; your boss needs to get the IT budget approved. That can result in strategically overlooking potential higher costs to get a solution approved.

Staying On-Premises

When indicators suggest public cloud isn’t right for your organization, how do you decide whether to move on or stay? The cost equation seems simple: effort + migration cost (-funding and credits) < license increase

But this ignores intangibles such as sentiment. In social media, sentiment is measured by analysing content to interpret attitudes toward a topic or brand. What I’m suggesting is a quantitative valuation of sentiment—based on measurable criteria.

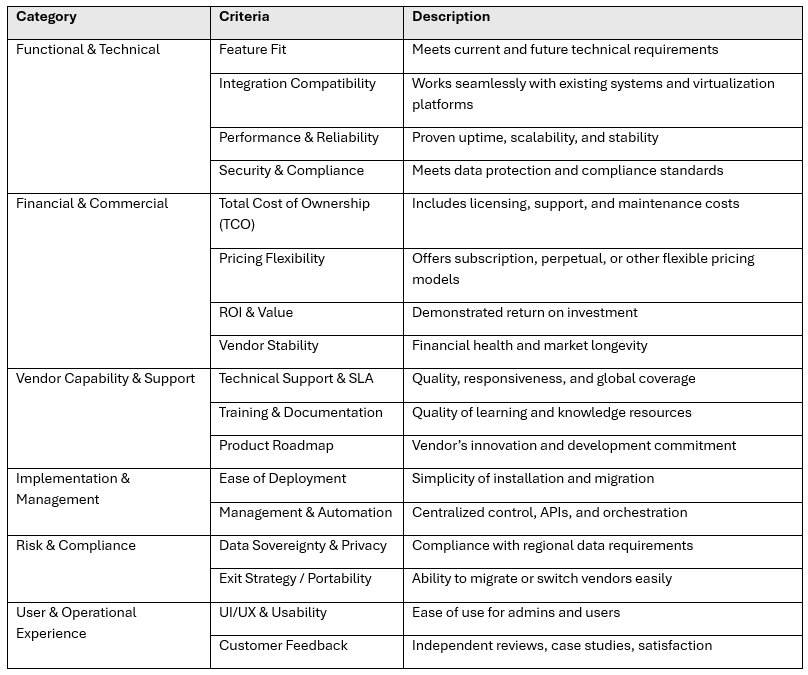

Let’s start with why your organization is exiting VMware. It’s not a technical issue, but it will have technical and financial implications, so the decison requires mutiple inputs. I asked ChatGPT to create a vendor evaluation checklist, and it produced these categories and criteria.

While there is a section on Vendor Capability and Support, specific focus on sentiment was missing, yet this is one of the most important factors in any choosing a brand.

-

Trust –will the vendor hold you hostage, your infrastructure and software critical are to the business, does the vendor make decisions that have a negative impact, in such a way that you have few options and no time to react? Is there flexibility in negotiations, indicating a willingness to meet you half way? How would you describe the relationship, positive, neutral or negative?

-

Predictability – each renewal should not be a time of uncertainty and fear, do you have contractual terms to ensure costs won’t significantly increase, or are you at the mercy of the vendor? What’s the historical reputation of the vendor, are they likely to hike prices, leveraging your dependancy on them?

I’m spending a lot of time looking at the alternatives to VMware. I’ve been impressed with the conversations I have had with Nutanix. For example at recent .Next events I was invited to some closed-door sessions with the CTO and engineering teams, most of whom are ex VMware, now these are the guys who have been pushing hyperconverged and trying to get us to give up our beloved storage arrays, to hear them say they are willing to put in the engineering hours because what some customers want is to continue with external storage, made an impression on me.

Yes, Nutanix’s integration with third party storage has its constraints, IP only (NAS, or iSCSI) for now only Dell, with Pure about to GA shortly, but these are engineering driven constraints not punitive measures designed to drive up revenue. As the price point for non-converged software will be lower, this is putting them on the opposite direction to VMware, more customers at lower revenue, that’s a strain on engineering and support, but says a lot about the brand.

#MCExperts, #MCX